I have always had a weakness for tarot and oracle decks because I love to see the different artistic interpretations applied to each card. But, as anyone who is interested in them knows, the market has become really glutted with decks over the last few years, to a degree that its hard to maintain any excitement for them (at least for me). There are a few exceptions to that though and this deck was one of them. When I first heard that Danu Forest and Dan Goodfellow were putting out a Celtic themed deck I was intrigued, in part because I have long been a fan of Goodfellow's art, and love his style. Because of how overstuffed the market is I wanted to do a short review of this deck today to give other people a better feel for what the deck is and why its worth getting.

The deck came out at the end of October and is available from the usual sources, including amazon.

First let me just say that I was very impressed by the box the cards come in. That may seem like a strange place to start, but many companies have reduced the quality of the packaging for their decks, probably to save money, so its nice to get a deck that's in a really solid box. Usually when I get a deck I transfer it to a pouch if I intend to use it because I know the boxes will disintegrate in a bag or purse, but with this one I'm comfortable leaving it in the box. Honestly I took this as a good sign before I'd even looked at the deck.

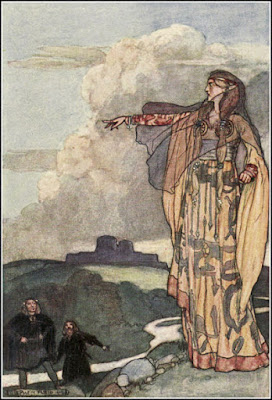

The deck itself is comprised of 40 cards, each featuring a figure from myth from one of the Celtic language speaking cultures. The card stock is nice and heavy, the cards a good size for shuffling, and each image is distinct. The art is beautiful, and in my opinion captures the overall feeling of each being depicted in the cards, which includes a range from figures like Boudica and Melusine, to the Morrigan and Artio. If you aren't familiar with Dan Goodfellow's art you can check it out here.

The deck comes with a paperback book, the same size as the cards, written by Danu Forest. Much more involved than the usual small booklet this runs 196 pages offering an in depth description of each card as well as a small section suggesting various spreads for divination. Each entry has a full color depiction of the card, the being's name, culture of origin, name pronunciation, a exploration of the figure it features in myth or folklore, suggested meaning in divination, and a short prayer. Its a much more thorough and informational book than I usually find with these kinds of decks and I really appreciated that. The author obviously put a lot of effort into research and tried to give readers a real feel for who these beings were and are.

Celtic Goddesses, Witches, and Queens Oracle is a wonderful combination of exceptional art and a thorough guidebook, making it an ideal divination option. The imagery is vibrant and evocative, allowing the cards to speak on their own, and the guidebook is a perfect compliment, expanding on the imagery and offering more depth to each figure. This deck could be used for various forms of divination but could also be an ideal devotional tool, helping people connect through story and prayer. The best option I've seen for this subject.