This article was originally written for my Patreon in 2023 and I am making it public now

Yesterday I gave a talk for the Folklore Podcast, as part of a lecture series to raise funds for the Folklore Library. My focus was tracing the history of the Scottish fairy courts across the last 500 years, from folklore to fiction. In the Q&A which followed someone asked a question about why we envision fairies as we do today and while I answered in the moment I thought I'd also offer a more expanded answer here for my patrons.

The short answer is, of course, the Victorians.

The long answer is that prior to the mid-19th century our understanding and perception of fairies was very different. They were not imagined with wings, or pointed ears, and were generally understood as being very human like in appearance, although not always in size, ranging from slightly less than two feet tall to around 6 feet tall (about 1/2 meter to 2 meters). The height often depended on the specific culture and the type of being, so that the Welsh Tylwyth Teg were described as 'the height of an 8 or 10 year old child' while the Irish Aos Sidhe were usually described as average adult height. Outside of this however there was rarely anything that physically distinguished these beings from humans, although they usually could be identified based on their words, actions, and a general aura of otherworldliness.

17th century woodcut showing fairies dancing in a ring

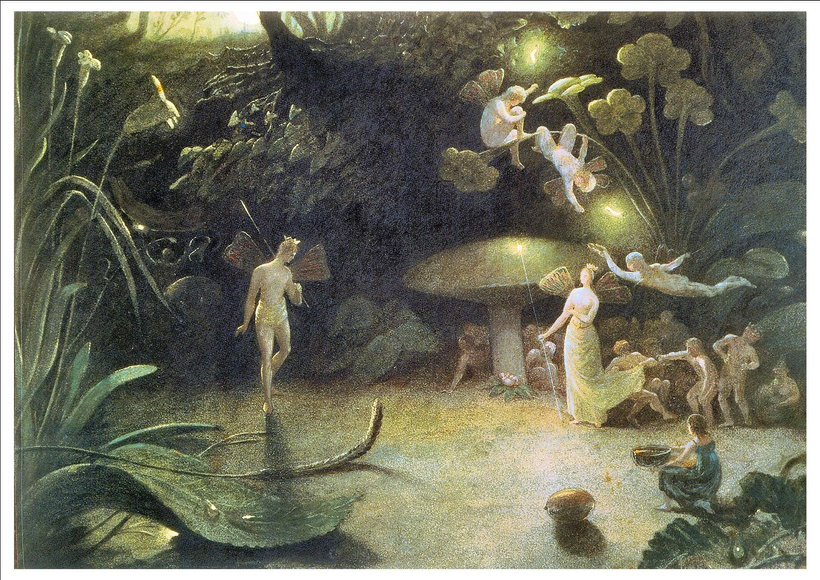

Henry Fuseli, 18th century, Titania and Bottom, showing the fairy queen Titania and her retinue of fairies with the donkey-headed Bottom

This began to change at some point in the early 19th century as fairies became popular in art and artists started depicting fairies with wings, and wingless elves with pointed ears. This may have been meant as a visual cue to viewers to make it clear the subject of the art were fairies or it may have represented a merging of the older understanding of fairies with the burgeoning idea of these beings as embodiments of nature and natural things, a concept which crystalized in the late 19th century with theosophies rewriting of fairies into elementals and nature spirits.

Initially however the change from non-winged fairies to winged wasn't decisive, and we see artists using both styles of imagery. For example the two following works by Francis Danby, the first of which from 1832 'Scene From a Midsummer Night's Dream' shows Oberon and Titania with wings while the second 'Oberon and Titania' from 1837 does not:

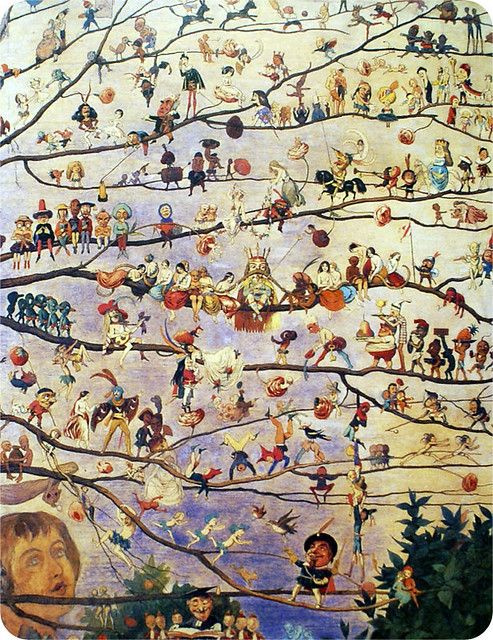

Through the 1870's we can find examples of fairies both with and without wings in art. For example this image 'The Fairy Tree' by Richard Doyle from 1865 shows 200 different fairy figures, none with wings, including several who appear to be flying:

By the 1880s however the wings dominate and can be found in all or nearly all artistic depictions of these beings. These wings are most often butterfly wings, occasionally more general insect wings, and range from small to larger than the figure itself. We also begin to see these visual cues used to gender these beings with female winged fairies and male elves with pointed ears, although there is some crossover between the two types of imagery.

It is also at this point that Theosophy begins, both taking the visual imagery of fairies found in art and also creating - or solidifying - the idea that fairies are spirits of the natural human world who are less than and dependent on humans. The combination of these two factors, Victorian cultural depictions and Theosophical descriptions, would combine to entirely rewrite the popular culture understanding of fairies in ways that are still effecting us today.

By the late Victorian era we find the idea of winged fairies, as shown in art, starting to crossover into fiction, and during the Edwardian period and first world war the wider cultural concept of fairies as small, winged, and connected to the natural world becomes nearly ubiquitous in English and American culture so that by the late 20th century people start to describe personal encounters with small winged fairies.

We shouldn't underestimate the power of art and fiction to shape folk belief, and be aware of how the media we consume influences our understanding of these beings.

References:

Fairies in Victorian Art by Christopher Wood

Victorian Fairy Paintings edited by Jane Martineau